Composer "provide" and dependency inversion

Matthias Noback

This is a response to Peter Petermann’s article Composer and virtual packages. First, let’s make this totally clear: I don’t want to start an Internet war about this, I’m just pointing out some design issues that may arise from using Composer’s provide option in your package’s composer.json file. This means it’s also nothing personal. To Peter: you wrote a very nice article and shed light on an underused feature of Composer. Thank you for that!

The situation Peter describes is a library that makes use of the LoggerInterface as defined in PSR-3:

namespace Example\MyLib;

use Psr\Log\LoggerInterface

class SomeClass

{

public function __construct(LoggerInterface $logger)

{

...

}

}

This LoggerInterface is readily available as part of the psr/log package. So this library explicitly mentions this package as a dependency:

{

"name": "example/mylib",

...

"require": {

"psr/log": "~1.0",

}

...

}

Peter then says:

[…] since you are building your lib so it needs a log provider injected (and if it is a NullLog), you want your dependencies to reflect that.

This is both true and false. Yes, if a user wants to run the code in your library, they need to have some class that implements LoggerInterface. But no, this shouldn’t be reflected in the dependencies of the library. Let me explain this by taking a look at the Dependency inversion principle.

Why we depend on interfaces: dependency inversion

We could have chosen to require one specific logger, for example the Zend logger (or the Monolog logger, or Drupal Watchdog if you like). Our code would have looked something like this:

namespace Example\MyLib;

use Zend\Log\Logger

class SomeClass

{

public function __construct(Logger $logger)

{

...

}

}

We’d have to reflect this in our list of dependencies of course:

{

"name": "example/mylib",

...

"require": {

"zendframework/zend-log": "~2.0",

}

...

}

Now we can do a little bit better, by depending on the interface Zend offers, instead of the class. This would allow others to implement their own logger class, which implements the Zend logger interface (maybe it can be an adapter for their own favorite logger).

namespace Example\MyLib;

use Zend\Log\LoggerInterface

class SomeClass

{

public function __construct(LoggerInterface $logger)

{

...

}

}

But it doesn’t really make a difference, since people would still have the zendframework/zend-log package pulled into their project for (almost) nothing.

To solve this issue, we may apply the Dependency inversion principle here. We want to invert the direction of our dependencies. We can do this in two different ways.

Solution 1: define your own interface

The first way is to define our own Logger interface, inside the library:

namespace Example\MyLib;

interface LibraryLoggerInterface

{

...

}

class SomeClass

{

public function __construct(LibraryLoggerInterface $logger)

{

...

}

}

One advantage of this approach is that we can define only the methods we need. A big disadvantage is that if we do this for each and every dependency we will end up with a lot of interfaces in our library, which requires you to also write a lot of adapter classes to make existing implementations conform to those interfaces.

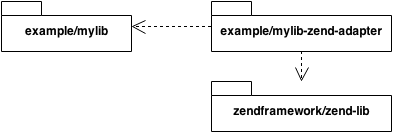

But still, in the example above we did invert the dependency direction. We started with this:

Then, we introduced our own LibraryLoggerInterface and this effectively removed any dependency arrow outwards. We introduced an adapter package which makes the Zend logger compatible with our logger interface. Looking at the modified dependency graph, we see that it contains a new dependency arrow, but this one points towards our library package:

Solution 2: decide on a common interface defined elsewhere

To overcome the problem of needing numerous adapter packages before we can finally start to use a library in our application, we can also try to define some common interfaces for things every library uses/needs. This is where PSR-3 steps into the picture. It tries to offer something very much like dependency inversion: a general logger interface which does not come with any concrete implementations.

This psr/log package is a highly abstract, independent, and therefore very stable package. It doesn’t tell you anything about how to implement a fully functional logger. Our example/mylib package therefore only depends on abstract things, instead of concrete things, which is what the Dependency inversion principle is all about.

Back to to square one: Composer’s provide

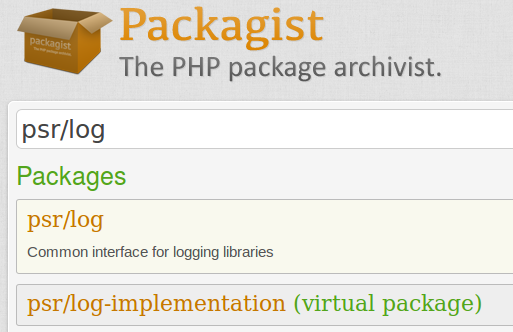

That was quite a bit of theoretical background. Now, back to where this all started: Composer has this feature which allows you to tell what kind of “virtual packages” a package provides. In the case of the psr/logger there are multiple logger packages that provide an implementation of the LoggerInterface from that package. These packages mention in their composer.json that they provide a psr/log-implementation package (you can find a list of PSR-3 compliant logger packages here):

{

"provide": {

"psr/log": "1.0.0"

}

}

This is a really cool feature. Especially since you can just “define” any virtual package by mentioning it under your own provide key.

But you have to think very hard before you use this provide feature. Peter suggests that the example/mylibrary package should not only have psr/log as a dependency, but it should also depend on the virtual package psr/log-implementation:

{

"provide": {

"psr/log": "1.0.0",

"psr/log-implementation": "1.0.0"

}

}

He thereby wants to communicate that in order to use this library, you also need a package which offers an implementation of LoggerInterface from psr/log. I don’t think this is a good idea (as you might have guessed ;)). These are my reasons:

- Strictly speaking (as in, would the code compile), the code from the library itself doesn’t need a package that provides

psr/log-implementation. It just needs theLoggerInterface(which happens to be in thepsr/logpackage). - Of course, in order to actually run the code from the library you will need an instance of

LoggerInterface, which means you need a class that implements said interface. But that doesn’t mean you actually need a package that contains such a class. That class can be located anywhere, in the current project, in a globally installed PEAR package, in a PHP extension, it may even be shipped with PHP. If you want to communicate that your library needs a working logger implementation, just using theLoggerInterface- and thus requiring justpsr/log- is quite enough. - By depending on an implementation package, you basically undo any effort you made to depend on abstractions and not on concretions. Since a “PSR logger” implementation is by definition a concrete implementation of the

LoggerInterfacefrompsr/log. In other words, you have pointed your previously inverted dependency arrow back to concrete packages (although you leave it undecided which concrete package that will be). psr/log-implementation, or any virtual package for that matter, is very problematic as a package. There is no definition of this virtual package. It is merely a phenomenon arising from the fact that some package has the name of the “virtual package” in itsprovidesection. In the case of thepsr/log-implementationpackage, this lack of a proper definition or rules for virtual packages means that there can a) be packages that contain a class that implementsLoggerInterface(frompsr/log), but don’t have"provide": { "psr/log-implementation": ..." }in theircomposer.jsonand b) that packages might say they provide, while they don’t. Which makes the concept unreliable.- Some day, someone may decide to introduce another virtual package, called

the-real-psr/log-implementation(they can easily do that, right?). Such packages may be completely exchangeable with existingpsr/log-implementationpackages, but in order to be useful, every existing PSR-3 compliant logger package needs to mention that virtual package too in theirprovidesection. And so on, and so on. The underlying conceptual problem is: there is no such thing as a canonical virtual package. - The notion of an “implementation package” is really vague. What does it mean for a package to be an implementation package. Is it sufficient for it to implement just one interface? What if the “interface package” contains multiple interfaces, which one should the “implementation package” implement? All, one?

- The final argument against

psr/log-implementationpackages is thatpsr/log(the interface package) itself contains aNullLoggerclass, which is an implementation of its ownLoggerInterface, and therefore this package itself also qualifies as apsr/log-implementationpackage!

But then, when should I use provide?

Now after being so negative about virtual packages, I am obliged to give you some positive examples of using virtual packages.

When the package knows about existing virtual packages

One interesting legitimate example I came across was the DoctrinePHPCRBundle. The bundle offers a Symfony-specific configuration layer for using PHPCR ODM with one of the existing PHPCR implementations (don’t ask me what all these words mean, since I don’t know much about them ;)). The actual PHPCR implementations packages jackalope/jackalope and midgard/phpcr both provide the virtual package phpcr/phpcr-implementation.

From the perspective of the DoctrinePHPCRBundle it makes sense to use virtual packages, since it actually knows about the existing phpcr/phpcr-implementation packages and it allows users of the bundle to pick one of them. Whether you choose the midgard/phpcr or jackalope/jackalope implementation package, the bundle knows how to correctly configure services for them.