Talk review: Thomas Pierrain at DDD Africa

Matthias Noback

As a rather unusual pastime for the Saturday night I attended the third Domain-Driven Design Africa online meetup. Thomas Pierrain a.k.a. use case driven spoke about his adaptation of Hexagonal architecture. “It’s not by the book,” as he said, but it solves a lot of the issues he encountered over the years. I’ll try to summarize his approach here, but I recommend watching the full talk as well.

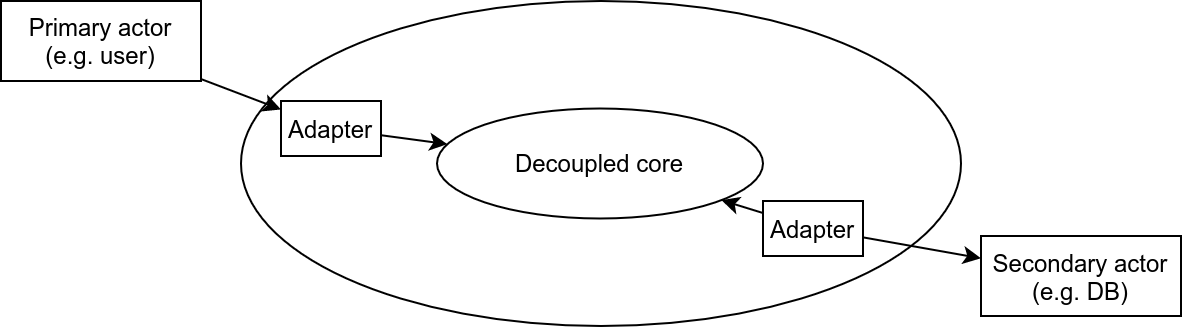

Hexagonal architecture

Hexagonal architecture makes a distinction between the use cases of an application, and how they are connected to their surrounding infrastructure. Domain logic is represented by pure code (in the FP sense of the word), surrounded by a set of adapters that expose the use cases of the application to actual users and connect the application to databases, messages queues, and so on.

The strict separation guarantees that the domain logic can be tested with isolated tests (“unit tests”, or “acceptance tests”, which run without needing any IO). The adapter code will be tested separately from the domain logic, with adapter tests (“integration tests”). Finally, when connecting domain logic and adapters, the complete running application can be tested with end-to-end tests or exploratory tests.

Pragmatic hexagonal architecture

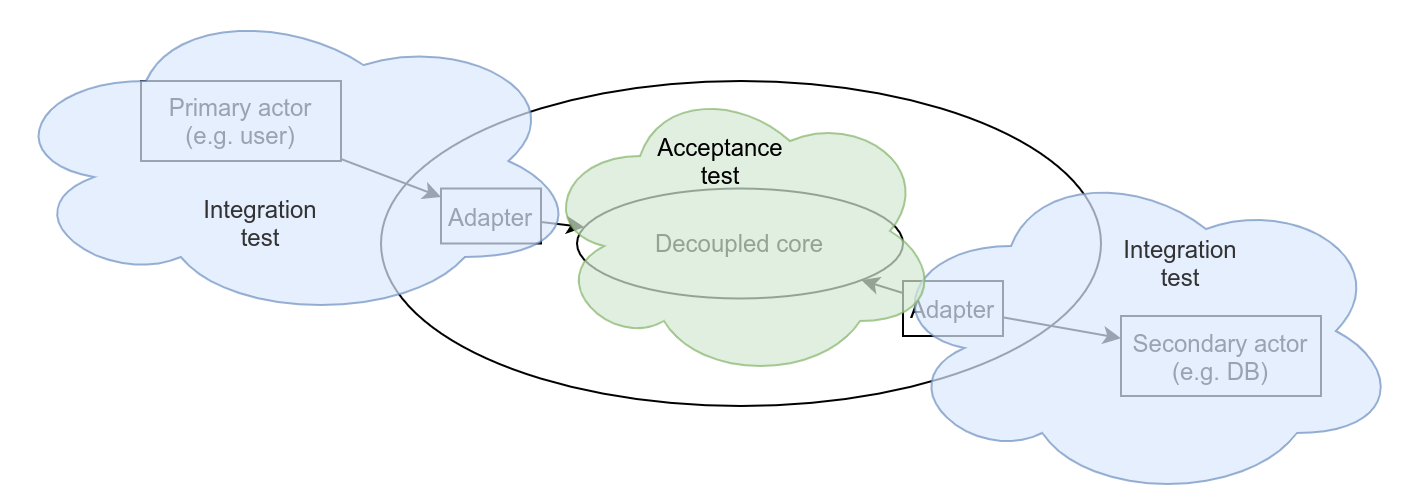

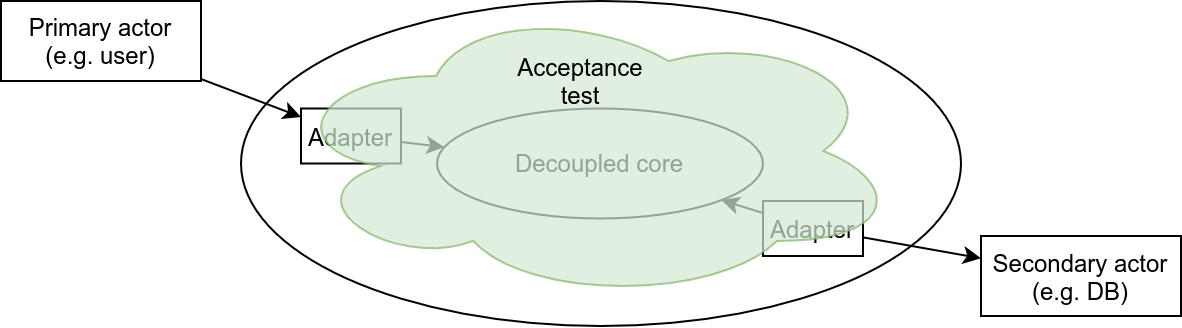

Thomas notes that in practice, developers like to write unit tests and acceptance tests, because they are fast, and domain-oriented. Adapter tests are boring (or hard) to write, and so they are often neglected. Thomas noticed that the adapters are where most of the bugs reside. So he stretches acceptance tests to also include part of the left-side adapters and part of the right-side adapters. Only the actual IO gets skipped, because the penalty is too high: it would make the test slow, and unpredictable.

I think it’s somewhat liberating to consider this an option. I’ve also experimented with tests that leave out the left-side adapter but include several right-side adapters. I always felt somewhat bad about it; it wasn’t ideal. Indeed, it may still not be ideal in some situations, but at least it gives you some options when you’re working on a feature.

I find I often don’t test left-side adapters on their own, so they are a nice place for mistakes to hide until deployment. Being able to make them part of an acceptance test is certainly a way to get rid of those mistakes. However, the standard arguments against doing this still hold up. Your acceptance tests become tied to the delivery mechanism. By invoking your web controller in an acceptance test, you’re coupling it to framework-specific and web-specific classes. This is going to be a long-term maintenance issue.

The same goes for the right-side adapters. If we are going to test part of those adapters in an acceptance test, the test will in fact end up being coupled to implementation logic, or a specific database technology. Thomas mentions that only the “last mile”, the actual IO, will be skipped. I took this to mean that your test may, for instance, use the real repository, but not provide the real database connection to it. This, again, seems like a very valuable technique. It saves some time creating a separate adapter test for the repository. However, this also comes at the price of increased coupling. The acceptance test verifies that a certain query will be sent to the database, but this will only be useful as long as we’re using this particular database.

Thomas explains that we can reduce the coupling issue by making assertions at a higher abstraction level, but even then, the acceptance tests being tied to specific technologies like that greatly reduces the power that came with hexagonal architecture: the ability to swap adapters, or experiment with alternative adapters, while leaving the tests intact. On the other hand, it is cool to have the option to write fewer types of tests and cover more or less the same ground.

Concerns

Although the concept of an acceptance test gets stretched a bit, it still doesn’t invoke any IO, which means it’s still mostly follows the hexagonal architecture approach, where we should be able to replace left-side adapters with our test runner, and replace right-side adapters with some fake adapters. However, when an acceptance test is also allowed to invoke (part of) the real left-side and right-side adapters, another aspect of hexagonal design is in danger: the possibility that the ports of the application aren’t fully decoupled from their adapters. For example, given your web controller accepts a Request object, you have to pass it as an argument in your acceptance test too. From the standpoint of the acceptance test, there is no guarantee that this Request object won’t get passed to an application service or even to an entity. The same goes for the right-side adapters. There is no guarantee that it’s the application service or the entity that talks directly to database connection.

Is this a bad thing? Well, not if you already want to have a decoupled application core and you’re aware of all the dangers of not having it. You’ll work hard to decouple, and won’t make mistakes like this. However, if there is substantial “coupling risk” in your team, you may still want to stick to acceptance tests that only invoke domain logic, and no adapters at all. I think this is what Thomas hints at when he mentions that his approach may not be for everyone, and that it’s his long time experience with testing that allows him to take these shortcuts. He has observed an increase in quality of the delivered software, so I think it’s fair for others to consider it too. After all, doing hexagonal architecture by the book doesn’t guarantee that you end up with something good, considering the development effort that went into it, how maintainable the end result is, etc. You’ll always need to be able to tweak aspects of your development work, optimizing its results. Thanks, Thomas, for giving us some more options in this area!