A wave of command buses

Matthias Noback

Recently many people in the PHP community have been discussing a thing called the “command bus”. The Laravel framework nowadays contains an implementation of a command bus and people have been talking about it in several vodcasts.

My interest was sparked too. Last year I experimented with LiteCQRS but in the end I developed a collection of PHP packages known as SimpleBus which supports the use of commands and events in any kind of PHP application (there is a Symfony bridge too, if you like that framework). I also cover the subject of commands, events and their corresponding buses extensively during my Hexagonal Architecture workshop.

Since I consider this topic to be a very important and highly relevant one, I will spend several blog posts on it, explaining the concepts in my own terms, then introducing SimpleBus as a ready-made solution for your everyday PHP projects.

What is a command?

Commands are often used in applications that separate the technical aspects of user input from their meaning inside the application. Commands in object-oriented programming are objects, like everything else. A command is literally some kind of an imperative, indicating what behavior a user, or client, expects from the application.

Commands can be very simple like StartDiscussion, SortList, SignUp, etc. They contain all the information the

application needs to fulfill the job. For example, the SignUp command could be a simple class like this:

class SignUp

{

private $emailAddress;

private $password;

public function __construct($emailAddress, $password)

{

$this->emailAddress = $emailAddress;

$this->password = $password;

}

}

A part of the application which is very close to the user itself creates an instance of this class and populates it based on values that the user provides. For instance, in a web controller, it might look like this:

class UserController

{

public function signUpAction(Request $request)

{

$command = new SignUp(

$request->request->get('emailAddress'),

$request->request->get('password')

);

...

}

}

Of course you could use a form framework to collect and validate the user data in a more orderly manner. Then the controller hands the command over to the part of the application which knows what to do with it (i.e. which is able to actually sign the user up). This thing that accepts commands is traditionally called a “command bus”.

...

$this->commandBus()->handle($command);

Advantages of using commands

The user is not being signed up right here and now, at this exact place in the code. Instead, the command bus is trusted to do the actual work. This comes with several advantages:

- The command might be created anywhere and by any client; as long as you hand it over to the command bus, it will be handled properly.

- Your controller doesn’t contain the actual sign up logic anymore.

The first advantage is pretty big. It should be extremely easy to create a console command in whatever way your framework wants you to do that, and achieve the same thing as in the web controller:

class SignUpUserConsoleCommand extends ConsoleCommand

{

public function execute(Input $input)

{

$command = new SignUp(

$input->getArgument('emailAddress'),

$input->getArgument('password')

);

$this->commandBus()->handle($command);

}

}

It doesn’t matter who creates the command, or when, or even where. It will always trigger the exact same behavior in the application.

The second major advantage is that your controllers don’t contain so much logic anymore. They merely translate the actual HTTP request to a corresponding command object, then let the command bus handle it.

Why is that a good thing? Well, first of all, this makes sure that none of the characteristics of the input side of your application (i.e. forms, query parameters, command-line arguments, etc.) leak to the core of your application. The core, or what lies behind the command bus, becomes totally ignorant of the world outside.

Before we introduced commands, the actual work was done in controllers. When you wanted to know what it meant for the business to “sign up a user”, you just needed to take a look at the controller which had that particular responsibility. However, by putting the sign-up logic in a controller, you tied this particular responsibility to the actual web UI. To sign up a user is not necessarily a web thing. In fact, it should be possible to do the same thing in a different way, for example from the command-line or from inside a script that does a batch import of users.

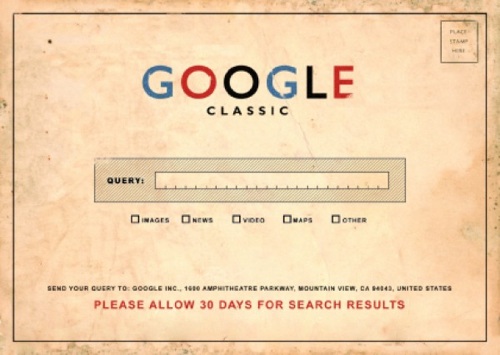

By using commands you make this possible: everything can be accomplished from anywhere, not just from controllers. Which is completely true to your business domain. If it would be possible to feed your application post cards, your customer would have wanted you to make it so.

Who handles a command?

A short summary of what we discussed so far: if you use commands to let the user communicate the application’s intended behavior, you make the core of your application completely unaware of the world outside. And on top of that, you separate the intended behavior from the actual implementation of that behavior.

The remaining question is: where do we find the actual implementation for a particular use case? The answer is: inside command handlers, like this one:

class SignUpHandler

{

public function __construct(UserRepository $userRepository)

{

$this->userRepository = $userRepository;

}

public function handle($command)

{

$user = User::signUp($command->emailAddress, $command->password);

$this->userRepository->add($user);

}

}

The command bus has a mechanism, hidden from sight, which finds the right handler for any command it handles.

Commands and handlers have a one-to-one correspondence. A command is always handled by one handler and one handler only.

All the commands inside an application together form a large and insightful catalogue of all the use cases that your

application offers. Browsing through a list of the available commands, you should be able to quickly notice what the

application is about and in what ways it can be influenced from the outside. Consider for example CreateIssue,

PickUpIssue, EstimateRemainingTime, MarkAsDone, etc.

Conclusion

Traditionally, the behavior of a web application would be defined by the controllers (and actions) that it offers. Routing definitions expose this behavior to the world outside. The principal way of talking to such an application is via the web.

Using commands you can separate the web-specific parts of your application from its essence. Commands define the use cases of your application and provide an internal API for anyone that might want to do something with your application.

Commands are not handled on the spot, but their behavior is implemented in command handlers. They are called by something called the “command bus”. In the next post we will look at what this mysterious command bus looks like and what its responsibilities are.