A collection of more than 250 articles about Software Design & Development Best Practices.

With code samples for PHP/Symfony and Fortran applications.

Fortran - Testing - Improving the design of the test framework - Part 2

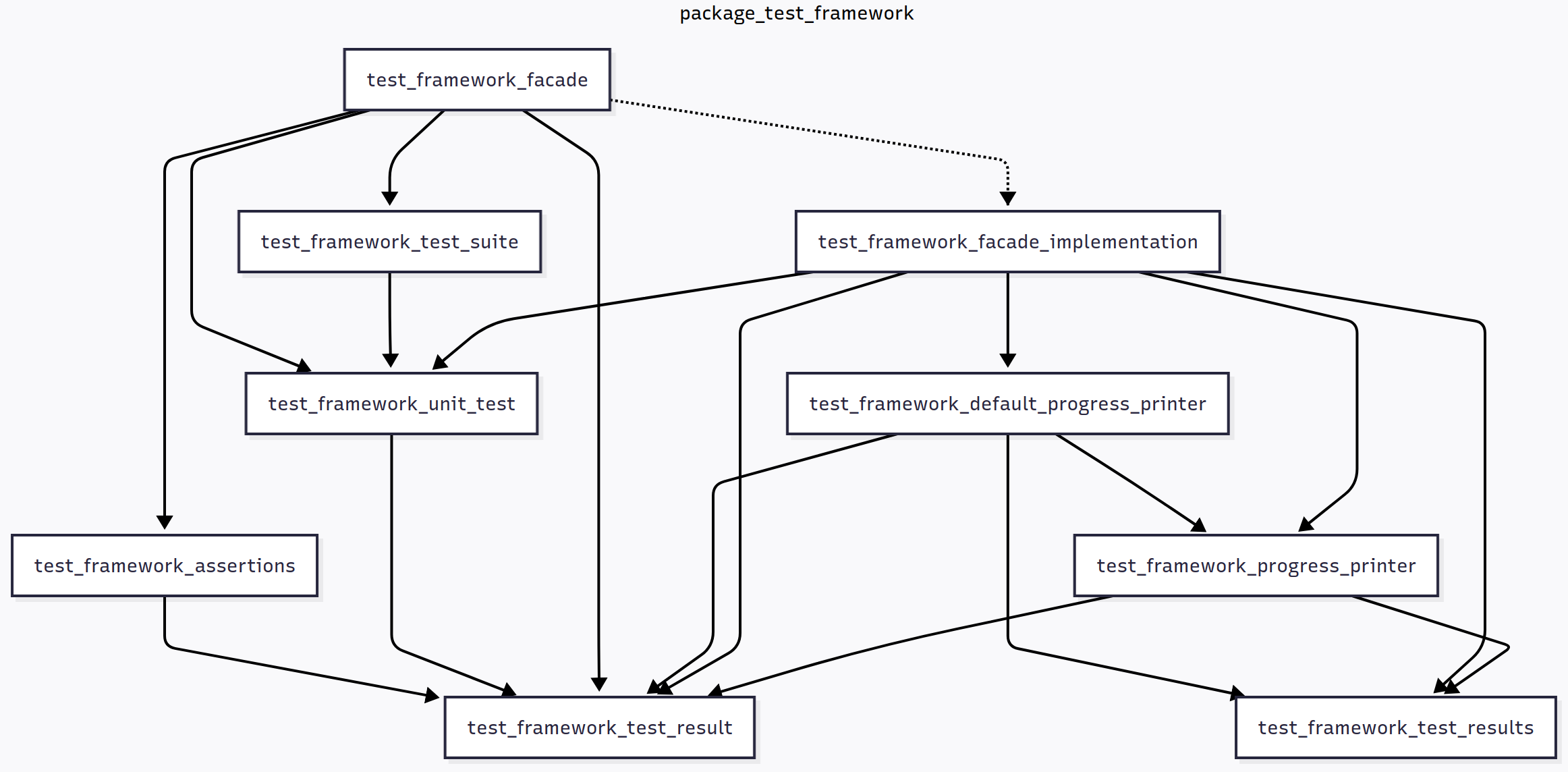

Several articles later, it turns out the little test framework has grown very fast. We’re looking at around 400 lines of code in a single test_framework module. In my opinion, this requires too much scrolling and jumping through the code to understand what’s going on or make changes. I’m aware “real-world” projects suffer from files that are a lot larger, but they are in a lot of trouble because of it. It’s smart to split large modules into smaller ones at a much earlier stage. As we discussed before, the following guidelines may be used when doing so:

Fortran - Testing - Improving the design of the test framework - Part 1

The right approach to software design, in my opinion, is to work with what you have, build more functionality on top of it, then realizing there are design issues, then fixing those issues by redesigning ad hoc. Where, in my experience, most software design efforts go wrong is:

- We realize there are design issues, yet we don’t fix them. Maybe it’s too scary.

- We fix design issues, but too early, when we can’t yet know if the new design is better. We lack feedback from actual use.

In this article series, I’m happy to report, I haven’t spent too much time designing upfront. But now I want to tackle some issues, that I encountered while adding more tests. Let’s look at one of our tests:

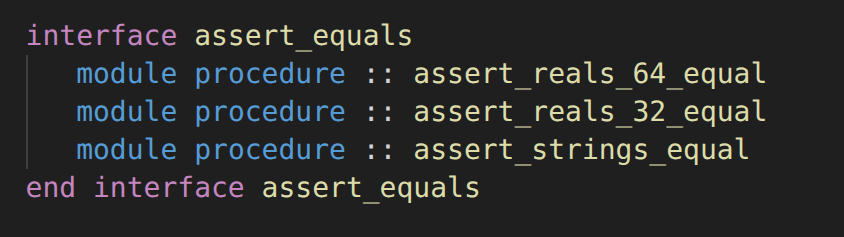

Fortran - Testing - More assertion functions

When expanding our test suite, we’ll certainly encounter the need for an assert_equals function that works with other types than real(kind=real64). We’d want to compare values of type logical, character, integer, etc. For example, say we have a utility function str_to_upper for which we are adding a unit-test in the test_string module. This function is supposed to convert the letters in a string to their uppercase alternative. The test looks like this:

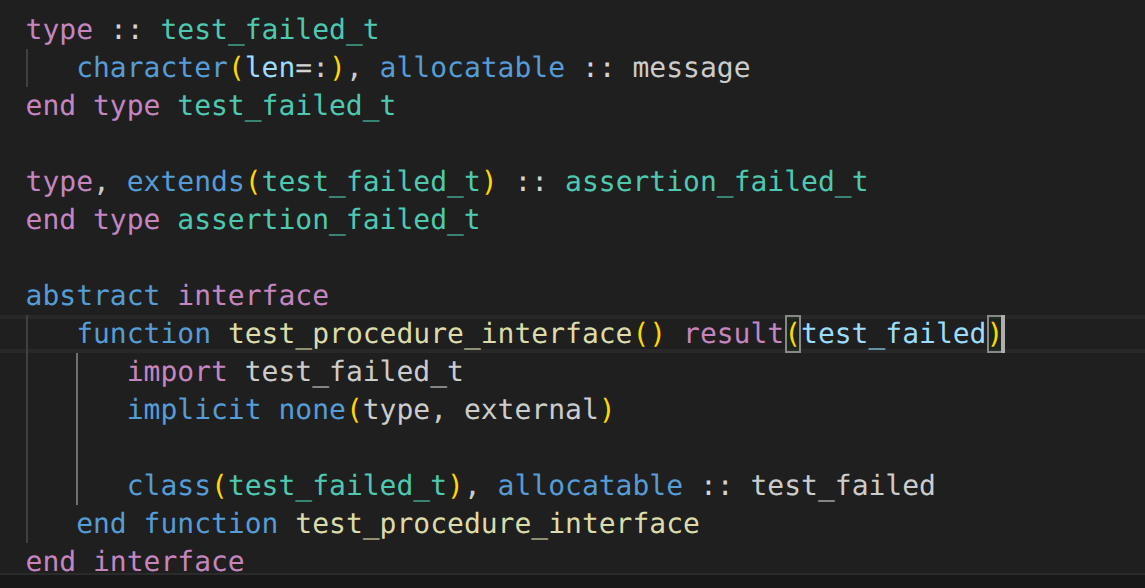

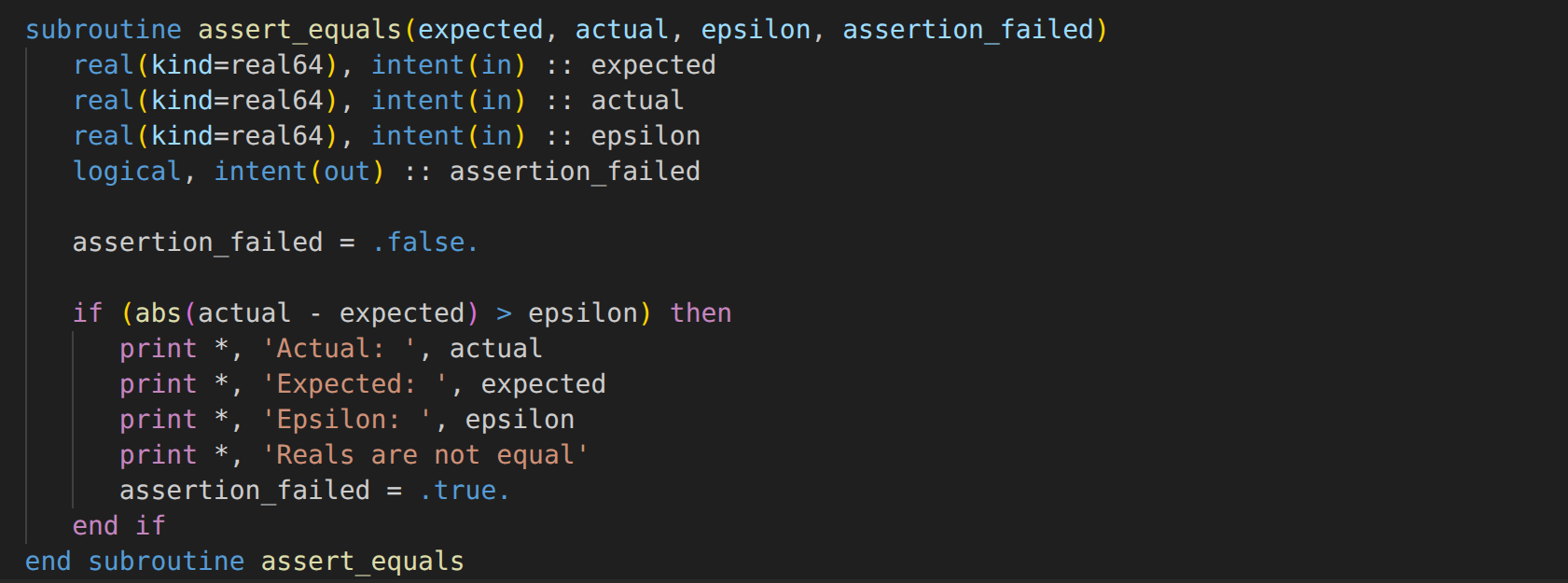

Fortran - Testing - Returning test and assertion errors

In the previous post we improved the output handling of the test runner, making output optional by using an abstract progress printer. Only our assert_equals function, which by the way should also be moved to the test_framework module, still prints directly to stdout:

function assert_equals(expected, actual, epsilon) result(assertion_failed)

! ...

assertion_failed = .false.

if (abs(actual - expected) > epsilon) then

print *, 'Actual: ', actual

print *, 'Expected: ', expected

print *, 'Epsilon: ', epsilon

print *, 'Reals are not equal'

assertion_failed = .true.

end if

end function assert_equals

To fix this, we should upgrade the return type. One idea would be to return a message (variable-length string) instead of a logical, but a more flexible, future-proof alternative is to define a custom type for an error. This would allow us to pass more information back to the caller than just the message. A suitable name would be assertion_failed_t:

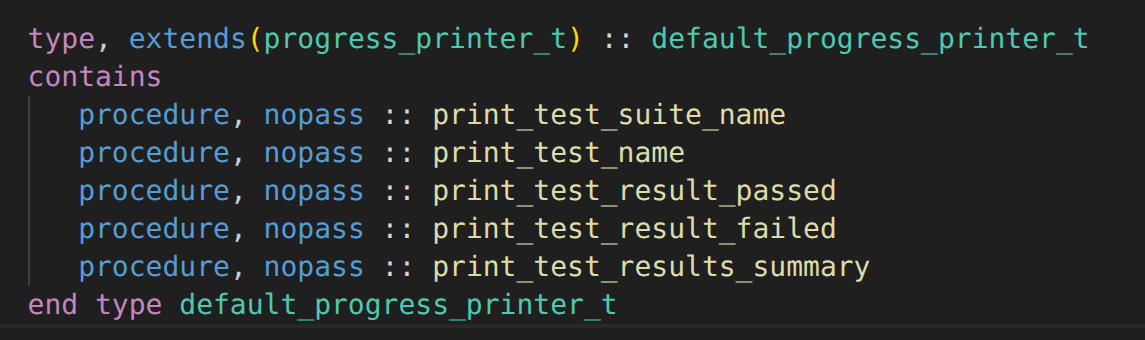

Fortran - Testing - Showing progress and printing results

In the previous post we’ve successfully split the running of the tests and collecting the test results from handling those results by printing the counters and error stop-ping the test program. We still ask each test procedure to print a small description. We do this to assist the programmer when there is some kind of crash during the test run: they need to be able to find out which test caused it.

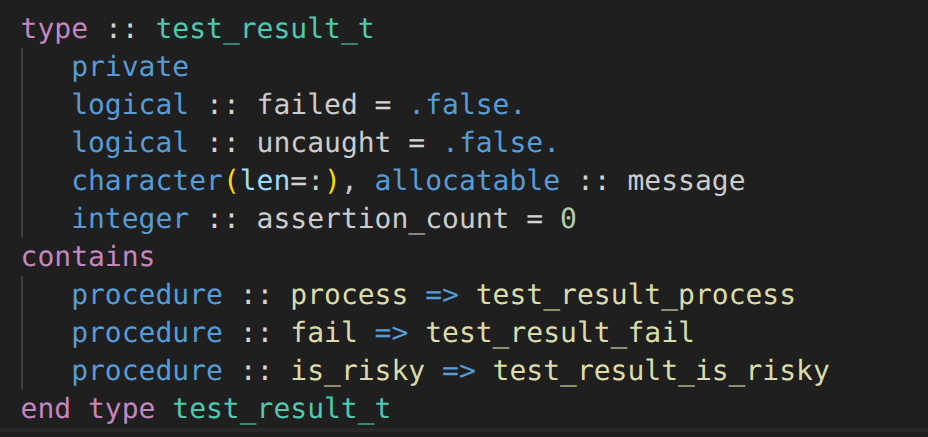

Fortran - Testing - Towards a generic, testable test runner

Maybe we’ve been writing more “generic” code for our custom test program than expected. We have been gradually, and quite safely, extracting code from a simple “check program”. But now that we’re looking at a pretty generic test runner that we’re going to use for all our future unit tests, we inevitably have to address the concern that we’re writing code that isn’t tested itself. Who tests the test framework? Well, the test framework itself has all the ingredients. However, testing the framework requires that we can run its code in isolation: that we can call one of its functions, and assert that it behaves correctly. Unfortunately, that isn’t possible yet. The code still lives in the main block of the tester program, and it doesn’t allow in-memory inspection of the test results, because it only prints them to the terminal, which we can’t unit-test.

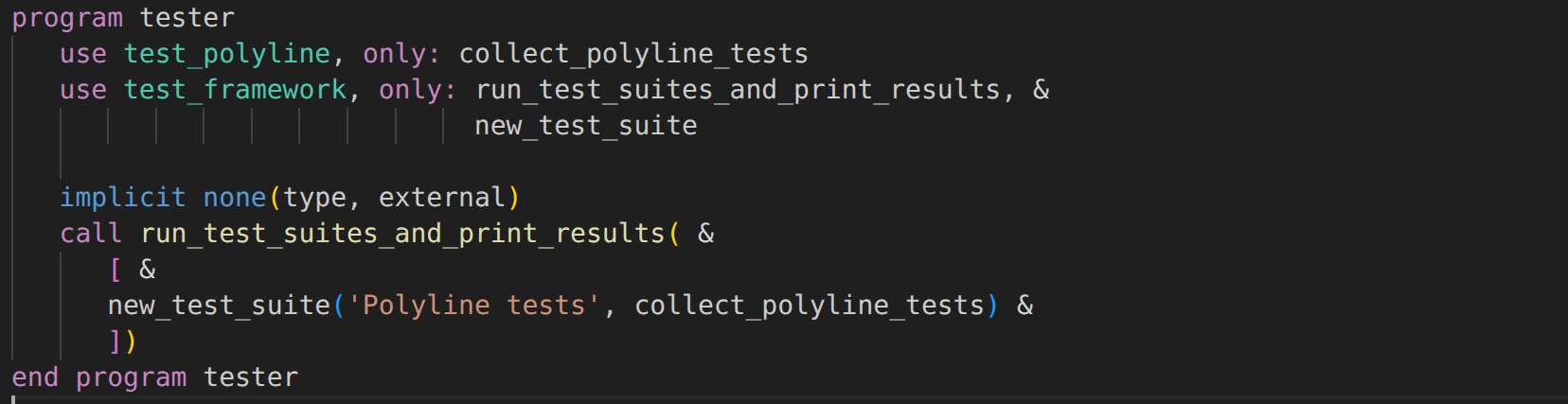

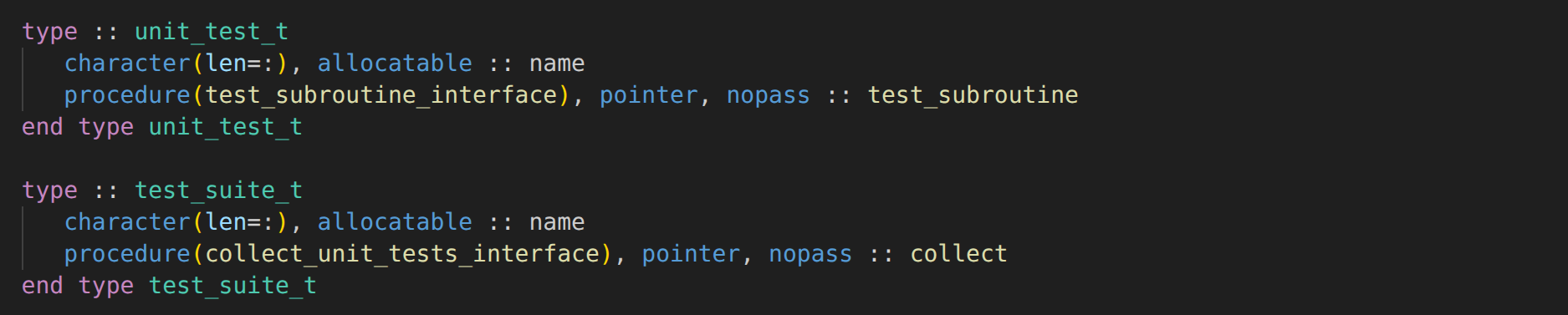

Fortran - Testing - Unit tests and test suites

In the previous post, we’ve spent some time improving a number of “temporary” tests. We introduced an assertion function to compare two real values, and we prevent failing tests from stopping the entire test program.

Moving tests to their own procedures

The approach of adding tests directly in the main test program block doesn’t really scale, as the saying goes. polyline_length may be a simple function, but for more complicated functions with multiple branches and loops, we’d have to write many of these tests. The test program keeps growing, and eventually it becomes a mess. It doesn’t help that all local variables have to be declared at the top. Even if that wasn’t needed, it isn’t very clear where a test starts or ends. Everything happens in the same scope, potentially becoming a memory management issue too. This also makes it hard to delete tests we no longer want. Removing lines from a big test program likely breaks other tests, or we forget to remove things we no longer need.

Fortran - Testing - Improving temporary test programs

How can we know that the function we wrote, works as intended? We could run it, and manually verify its correctness. The simplest way to do this is to call the function in the main program block, print the output, and compare it with what we expect. Say our function calculates the length of a polyline, stored as a two-dimensional array of reals, representing (x,y) coordinates:

pure function polyline_length(coordinates) result(length)

real(kind=real64), dimension(:, :), intent(in) :: coordinates

real(kind=real64) :: length

real(kind=real64) :: distance

integer :: index

length = 0.0_real64

do index = 1, size(coordinates, 1) - 1

distance = sqrt((coordinates(index, 1) - &

coordinates(index + 1, 1))**2 + &

(coordinates(index, 2) - &

coordinates(index + 1, 2))**2)

length = length + distance

end do

end function polyline_length

Temporary test programs

We could modify the main program block of our actual program, but it’s a lot simpler and safer to create a separate “throw-away” test program, with only the code we need. We’d write a short test program that sets up some coordinates, calls the function, then prints the result:

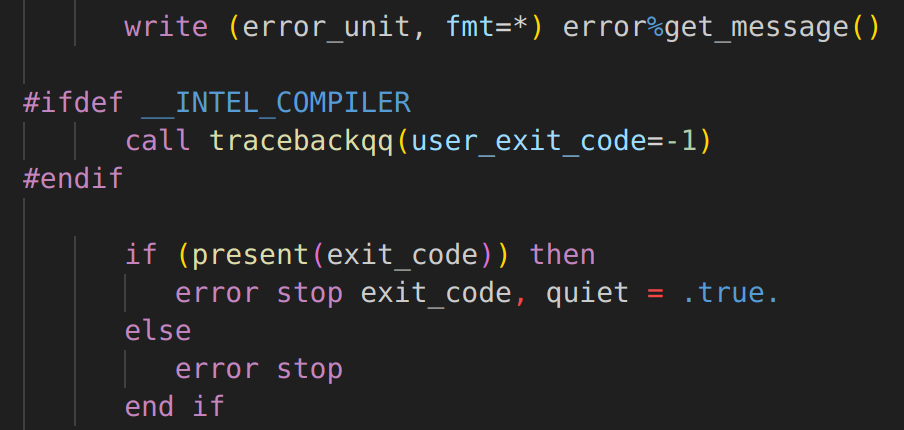

Fortran - Errors and error handling - Part 7 - Fatal errors

We’ve encountered several ways of designing functions in a way that allows them to fail for some reason, without stopping the program, or making it otherwise risky or awkward to use the function. We introduced the error_t type which is very flexible. It can be used to provide some information to the caller, helping them understand what went wrong and how it can be fixed. By allowing errors to be wrapped inside others, we can create chains of errors that describe the problem at various abstraction levels. It gives back control to the user: how do they want to deal with an error? Would they like to try something else? Or, in the end, should we just stop trying and quit te program?